- Home

- Kirsten Lodge

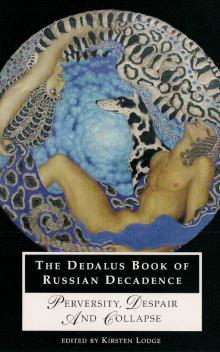

The Dedalus Book of Russian Decadence

The Dedalus Book of Russian Decadence Read online

This collection is dedicated to Oliver Lodge.

ABOUT THE EDITOR

Kirsten Lodge (Ph.D., Columbia University) is currently working on a book on decadence in central and eastern Europe. Her collection of Czech decadent poetry in English, Solitude, Vanity, Night, is forthcoming. She is also the author of Translating the Early Poetry of Velimir Khlebnikov.

ABOUT THE TRANSLATORS

Margo Shohl Rosen has published her translations of Russian literature in The London Review of Books, American Poetry Review, and most recently, Lions and Acrobats: Selected Poems of Anatoly Naiman.

Grigory Dashevsky, a professor of Latin at Moscow University, is a poet and a translator from English, French and German. His translations into Russian include Fr. Yates’s Giordano Bruno and the Hermetic Tradition, Z. Bauman’s Freedom (both from English) and Hannah Arendt’s Men in Dark Times (from English and German).

DISCLAIMER

Despite the best endeavours of the editors, it has not been possible to contact the rights holders of the texts in copyright. The editors would be grateful, therefore, if the rights holders could contact Dedalus.

Acknowledgements

I wish to express my gratitude to Ilya Vinitsky, who introduced me to Oliver Ready in 2004, thus initiating the chain of events that led to the publication of this anthology. I am thankful to Oliver for putting me in touch with Eric Lane at Dedalus Books, and to Eric for his enthusiastic support of the project from its inception. Thanks also to B. Tench Coxe for his suggestions for both the poetry and prose translations, and Grigory Dashevsky for carefully checking the translations of the poems against the originals and offering his comments. The translators are deeply indebted to Simon North for diligently combing all of the texts for Americanisms, Emily Mitchell for her assistance with colloquial British English in “Moon Ants” and “The Sting of Death,” and Craig Beaumont for acting as our consultant on British English. We also wish to acknowledge Frank Miller’s aid in rendering torture instrument vocabulary into English. Of course, we are fully responsible for any remaining deficiencies in the collection.

Kirsten Lodge

Contents

Title

Dedication

About the Editor and Translators

Disclaimer

Acknowledgements

Introduction

Valery Briusov: The Last Martyrs

Briusov: Oh, cover your pale legs!

Briusov: Presentiment

Briusov: Messalina

Briusov: Now That I’m Awake

Fyodor Sologub: For me alone my living dream

Briusov: The Slave

Sologub: Because she hadn’t studied hard…

Briusov: The Republic of the Southern Cross

Briusov: The Coming Huns

Briusov: We are not used to bright colours…

Briusov: Distinct lines of mountain peaks…

Sologub: The Sting of Death

Sologub: O death! I am yours…

Sologub: Since I fell in love with you…

Briusov: Hymn of the Order of Liberators in the Drama Earth

Sologub: The Poisoned Garden

Briusov: With a secret joy I would die…

Zinaida Gippius: Follow Me

Sologub: What makes you beautiful?…

Sologub: Light and Shadows

Sologub: My tedious lamp is alight…

Sologub: Death and sleep, sister and brother…

Sologub: You raised the veil of night…

Gippius: The Living and the Dead (Among the Dead)

Sologub: O evil life, your gifts…

Gippius: Everything Around Us

Gippius: The Earth

Gippius: Moon Ants

Sologub: To the window of my cell…

Gippius: Song

Gippius: The Last

Leonid Andreyev: The Abyss

Alexander Blok: I am evil and weak…

Dmitry Merezhkovsky: Children of Night

Sologub: Captive Beasts

Andreyev: In the Fog

Blok: What will take place in your heart and mind…

Gippius: Her

Merezhkovsky: Calm

Andreyev: The Story of Sergey Petrovich

Blok: On the Eve of the Twentieth Century

Blok: We are weary…

Blok: The moon may shine, but the night is dark…

Alexander Kondratiev: Orpheus

Blok: The Doomed

Sologub: God’s moon is high…

Merezhkovsky: Pensive September luxuriously arrays…

Kondratiev: In Fog’s Embrace

Gippius: Rain

Blok: The Unknown Woman

Gippius: Starting Anew

Kondratiev: The White Goat

About the Authors

Copyright

Introduction

The depravity and despair of decadence that burgeoned in France in the latter half of the nineteenth century had gripped all of Europe, including Russia, by the century’s close. Originating in the superbly refined and subtly perverse poetry of Charles Baudelaire, Stéphane Mallarmé and Paul Verlaine and finding its quintessential expression in Gustave Moreau’s sensual paintings of Salomé dancing for the lecherous King Herod, decadence gained widespread popularity in France in 1884 after the publication of Joris-Karl Huysmans’s novel Against Nature. Against Nature, which became known as “the breviary of the decadence,” gives expression to the movement’s fundamental tenets: that modern-day civilisation is in decline, that reality as it exists is contemptible, and that the decadent hero, who is neurotic and sexually deviant, must create an alternative world for himself alone. Des Esseintes, the main character of Against Nature, retreats to a house outside of Paris, where he has his surroundings constructed in accordance with his whims. The cabin of a ship, for instance, is built within his dining room, and he spends hours sitting inside it, watching mechanical fish swimming in an aquarium placed between the porthole of the cabin and the dining room window, so that the water subtly changes hue with the varying sunlight. He can thus pretend to be travelling and enjoying nature without having to deal with the annoyances and ugliness of reality. This image of pseudo-sailing exemplifies the decadent cult of the artificial: artifice for the decadents is superior to nature.

At the turn of the century decadence flourished in the work of Russian writers of various schools: hence this anthology groups Leonid Andreyev, who frequented Maxim Gorky’s Realist circle, and Alexander Kondratiev, who did not consider himself part of any school, with the other writers included here, who identified themselves primarily as Symbolists. Symbolism derived from the same French models as decadence, but it emphasised different thematic and stylistic concerns, evoking the poet’s inner world or a mystical world beyond our own through suggestion and the use of poetic symbols. More ambitious than their French counterparts, many of the Russian Symbolists hoped to transfigure the fallen world, which they found execrable, either by the power of their own creative will or with divine aid. However, their mood would vacillate from yearning for a miracle to black despair, and this is when they would enter into the decadent mode. In this collection, this sense of hopelessness after faith in an imminent miracle is most evident in the poetry of Zinaida Gippius and Alexander Blok. If the world could not be transformed, the alternative was to withdraw from it. For the decadents there were several ways to escape from deplorable life: these included the creation of art or an artificial environment, sexual deviation, madness and suicide. The authors included in this collection dramatise these various alternatives.

A powerful will is necessary to create an ideal environment, and the decadents’ worship of

the will is related to their stance of extreme individualism. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, it was widely believed that European civilisation was in decline, or “decadence”: that is, society was becoming increasingly fragmented. It was no longer unified by higher values, such as religion. Individuals were becoming increasingly isolated in an age of declining morals. Many deplored this fact, while others upheld individualism as a positive principle. Commentators frequently compared their age to the final days of the Roman Empire and predicted imminent collapse. Decadents also looked back to the Roman Empire for inspiration and found it not only in images of decay and decline, but also in the dramatic personalities of the cruel Roman emperors, whose every whim became reality. They became prototypes of glorified egoism, with their unbridled cruelty, perverse pleasures and excessive indulgences. Decadents often took individualism to the extreme of solipsism. Valery Briusov is a case in point. He believed that the individual could truly know nothing outside of himself—his own thoughts, feelings and desires. For Briusov it is even impossible to be certain that the outside world actually exists. The confusion of dream or fantasy and reality is thus central to many of his stories, including “Now That I’m Awake…” (1902).

In this dramatic tale of demonic savagery, egoism merges with sadism as the narrator gives full reign to his cruel fantasies—at least within an environment he believes to exist only in his imagination. He asserts that he has always preferred dreams to reality, and boasts that he has learnt to control his dreams. Above all, he likes to torture people in his dream world, never relinquishing control of the narrative of agony. However, the line between dream and reality becomes blurred: this is the diary of a psychopath.

“Art” and madness are likewise closely linked in Fyodor Sologub’s first published short story, “Light and Shadows” (1894). In Sologub’s story, young Volodya discovers art as a means to escape from the monotonous reality of school and the useless lessons he is forced to learn. After finding a booklet giving directions on how to make shadow figures on a blank wall, Volodya soon masters the examples provided and begins to create his own, more complex figures. He is driven to indulge in these creations at the expense of his schoolwork and even his health. Like a writer, he invents narratives, personalities and feelings for his figures. Soon, however, they take on their own, independent reality. He senses their unbearable sadness, and he is overwhelmed. Volodya’s obsession is contagious: his mother, too, begins to make shadow figures secretly in her room, and shadows soon start to pursue her as well.

Sologub is more optimistic about the power of art and the artist’s will in some of his poems. In “My tedious lamp is alight …” (1898), for instance, he prays for inspiration to create the perfect work, which will grant him immortality. The artist, he implies, has the potential to become a deity, and the creative will can work miracles. In “For me alone my living dream …” (1895), he imagines the sadomasochistic world of his dreams, established by force of will, and full of revelry, sex and whipping. The artist’s will is omnipotent, capable of transfiguring reality—or at least creating a second world within the realm of literature.

Of the various escape routes from reality, suicide is by far the most popular in these works by writers of a decadent bent. “O death! I am yours,” Sologub exclaims in a well-known early poem, rejecting life as unjust and disdainful. In his story “The Sting of Death” (1903), two friends nurture an ever-growing attraction to death, which one boy depicts as a comforting, faithful and beautiful lover. The poetic register of his description contrasts sharply with the colloquial language of the rest of the story. In “The Poisoned Garden” (1908), seductive death is personified as a femme fatale. The Beautiful Lady of this stylised tale is herself like the poisonous, carefully cultivated flowers of her garden, flowers that recall Des Esseintes’s attraction to horticulture and predilection for real flowers that appear to be artificial. This story demonstrates that Sologub shared with Oscar Wilde the decadent attraction to fairy tales as a genre divorced from reality. Within the fairy tale the writer is free to polish an artificial, archaic style and to use motifs and characters symbolically, without locating them within a specific historical context. The result is a stylistic gem sparkling with Beauty, Love and Death. At the same time Sologub’s story, published shortly after Russia’s failed revolution of 1905–07, is clearly concerned with class conflict. It is a rare example of a fairy tale mingled with Marxism, in which the main characters are revolutionary activists, each in their own way.

Charlotte of Zinaida Gippius’s “The Living and the Dead (Among the Dead)” (1897) is repelled by the physicality of life. She is disgusted by the sickliness of her brother-in-law and nephew, and above all by the prospect of marrying a butcher. She is nauseated by the bloody carcasses, flesh and bits of bone that fill the butcher shop where her fiancé indifferently slices meat with a butcher knife. She prefers to spend time alone in her room, where she observes the cemetery through blue stained glass that softens everything she sees. The delicate blue glass, which she associates with the cemetery and death, contrasts with the red and yellow glass in her father’s dining room—colours associated with the butcher shop. Fleeing the earthly world she despises, she dreams of the “light-blue world” of death, filled with peace and love.

Death is not always conceived in such mystical terms in Gippius’s work. The narrator of her “Moon Ants” (1910) strives to comprehend suicide, only to conclude that it is impossible to predict or understand. People may attempt suicide for the most insignificant reasons, and they may not even know why they have decided to kill themselves. The narrator of “Moon Ants” is astounded at how many people have been killing themselves recently, and he is obsessed with the phenomenon, which he traces back to the failed revolution. Had life in Russia at the turn of the twentieth century become so harsh and hopeless that it unleashed an epidemic of suicide? The narrator of “Moon Ants” offers an alternative explanation: people have become weaker—so weak, in fact, that they kill themselves at the slightest provocation. Like the moon ants in H. G. Wells’s novel The First Men in the Moon, they crumple up and die the moment they are touched.

It was widely believed at this time that humanity was degenerating. The theory of degeneration was a logical extension of Darwinism, which argued that evolution takes place in a natural environment. Proponents of degeneration theory such as Cesare Lombroso and Max Nordau reasoned that mankind was completely estranged from nature in modern society, and therefore removed from the life-threatening factors necessary for evolution by natural selection to take place. The comforts of urban life, they argued, were causing regression to earlier stages of development. Mankind was becoming weaker, sicklier and more prone to nervous ailments of all kinds. Nordau’s Degeneration (1892), published simultaneously in two Russian translations in 1894, became one of Europe’s bestsellers, fuelling popular fears with its warning of an epidemic of degeneration. The narrator of “Moon Ants” expresses similar qualms, imagining a plague of weakness and suicide to which he himself may fall prey. Many other stories in this anthology are also accounts of contagion leading to death. The contagion may involve the spread of ideas, as in “The Sting of Death,” or of disease, as in Leonid Andreyev’s “In the Fog” (1902). In addition, it was believed that asymmetrical facial features were symptomatic of degeneration, that it was hereditary and that artists were particularly degenerate; thus the irregular features Volodya and his mother share in “Light and Shadows” should be understood within the context of the European obsession with degeneration.

Andreyev treats the issues of lust and prostitution, which were considered to be symptomatic of degeneration, in the stories “In the Fog” and “The Abyss” (1902). In “In the Fog,” Pavel’s father, who, the author tells us, represents the prevailing views of his time, expresses his fear of “civilisation’s darker side.” He warns his son against phenomena typically associated with degeneration, including alcoholism and, above all, debauchery, which causes ven

ereal diseases that lead to debility, insanity and death. Pavel, however, feels he has already been corrupted. His “filthiness” permeates his entire being like the yellow fog outside, and he can escape neither one. Like his sense of being corrupted, his view of women is also typically decadent: he is attracted to them, but at the same time overwhelmingly disgusted and horrified by them, and he believes them all to be hateful, vulgar and deceitful. His misogyny is reflected in the fact that he completely forgets women—whether his mother or a prostitute—the instant he turns away from them.

In “The Abyss,” Andreyev shows what may happen when the veil of culture is suddenly lifted. A young couple on a walk, Nemovetsky and Zina, speak romantically of pure love and eternity until they are caught at dusk in a field among prostitutes and drunken men. An unfortunate incident entirely changes Nemovetsky’s perception of the young woman, and he falls into the “abyss” of irrational, bestial instinct. Like “In the Fog,” this story sparked controversy upon its publication; Andreyev’s explicit treatment of the themes of prostitution, venereal disease and rape were considered scandalous by some critics, while others defended him for bringing to light moral problems that society must address. When Lev Tolstoy’s wife berated Andreyev for depicting the most abject human degradation and slandering humanity in “The Abyss” rather than praising the miracle of God’s world, Andreyev responded that civility is deceptive, and beneath it lies a beast straining to devour itself and every living thing around it the moment it breaks out of its chains. It is impossible, he wrote, to “slander” a humanity that has on its conscience such heinous crimes as those committed during recent imperialist wars. Several years later, Andreyev vividly portrayed the cruelty and madness of war in his novella The Red Laugh, inspired by the shocking bloodshed of the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–5.

In “The Story of Sergey Petrovich” (1900), Andreyev applies his skill in describing a character’s psychological vacillations to an ordinary man who happens to have read some of Friedrich Nietzsche’s Thus Spake Zarathustra. We have heard a lot about men who read Nietzsche and think they are supermen, but what about those who realise they are part of the herd? As Andreyev wrote in his diary about the story, Nietzsche teaches Sergey Petrovich to rebel against injustice—against nature and humanity.

The Dedalus Book of Russian Decadence

The Dedalus Book of Russian Decadence